Christopher Columbus: When Did the Hero Become a Villain?

By Janice Therese Mancuso

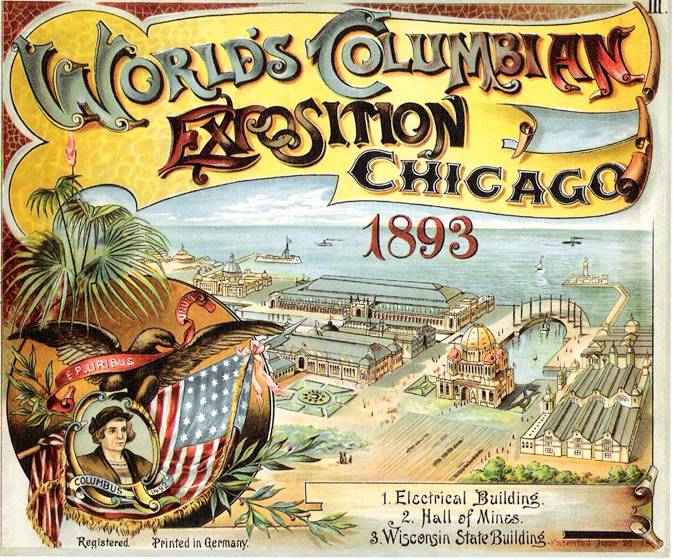

In 1892, Columbus was an American hero. President Benjamin Harrison proclaimed, “Friday, October 21, 1892, the four hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America by Columbus, as a general holiday for the people of the United States.” (The 21st reflected the change from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar in 1582.)

Columbus was honored over 100 years earlier, though, in 1775 when one of the first war ships of the newly formed Continental Navy was named after him. In moving away from Great Britain, the Revolutionary War was a turning point for a young nation; and after gaining independence and seeking a unifying bond for the United States of America, Columbus emerged as a representative – an adventurer – in leaving the old and discovering something new. As poems about Columbus circulated throughout the states, Columbus and Columbia were associated with liberty, and in 1791, the District of Columbia was founded as the new nation’s seat of federal government.

In August 1792, the cornerstone for the first monument in America dedicated to Columbus – an obelisk 44 feet tall – was set in Baltimore. (The base of the obelisk was damaged in 2017, and repaired; however, the plaque dedicating the monument to Columbus was not replaced.) That same year, for the 300th anniversary of Columbus’s landing, several cities held celebrations with the largest in New York City sponsored by the Tammany Society (at the time a social association).

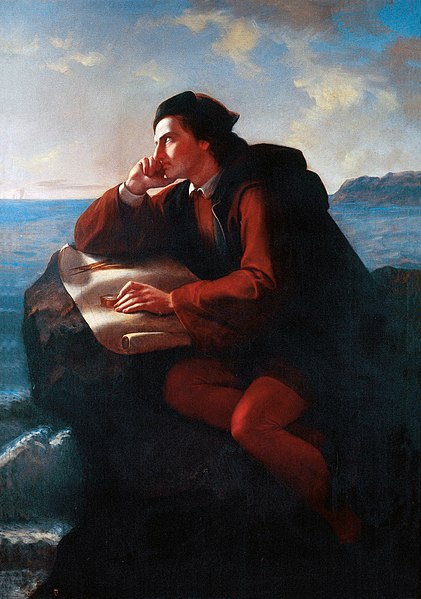

In the early nineteenth century, Columbus continued on a symbolic climb as an American icon; and Washington Irving – acclaimed for his widely-read literary and scholarly works – wrote The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, published in 1828. While researching and writing about Columbus, Irving, who was well-versed in Spanish, was living in Spain and had access to historical documents in the Spanish archives. (He would later become U.S. diplomat to Spain.) Released in several volumes, at the time, the book was considered an imperative detailed biography of Columbus.

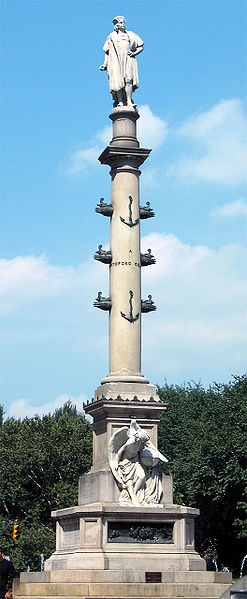

In 1849, Boston became the first city to display a statue of Columbus. In the following 100 years, statues of Columbus would be showcased in towns and cities throughout America, with one of the most well known standing tall in New York City since 1892, surrounded by Columbus Circle. (The 76-foot tall monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2018.) Columbus was also honored by Constantino Brumidi, “the Michelangelo of the Capitol,” who painted Columbus the Explorer on the ceiling of the President’s Room in the Capitol Building in the late 1850s. Around 20 years later, Lord Alfred Tennyson – at the time, Poet Laureate of Great Britain and Ireland – wrote the poem, Columbus.

As more Italians immigrated to America, although most were harshly discriminated against, they also became aware of the growing attention Christopher Columbus, a fellow Catholic Italian, was receiving and were soon celebrating him in annual events. The founding of the Knights of Columbus in 1882 brought even more awareness to a Catholic who was an important part of American history.

In 1891, The Life of Christopher Columbus from His own Letters and Journals and Other Documents of His Time by Edward Everett Hale was published. A journalist, Harvard graduate, and minister, Hale wrote in the preface, “This book contains a life of Columbus, written with the hope of interesting all classes of readers. His life has often been written, and it has sometimes been well written. The great book of our countryman, Washington Irving, is a noble model of diligent work given to a very difficult subject. And I think every person who has dealt with the life of Columbus since Irving's time, has expressed his gratitude and respect for the author.” (Hale’s great uncle was Revolutionary War hero Nathan Hale.) The following year, Sir Clements Robert Markham – an English explorer, geographer, and writer – wrote The Life of Christopher Columbus.